When one has the privilege to chance upon architecture that has been in existence for thousands of years, one is often mesmerized by the level of dexterity, precision and articulation achieved, particularly since it was without the use of modern power tools or machinery. A detailed study of the historical architecture of these buildings would provide conclusive evidence that their design evolved through generations of experimentation with various creative ideas, multiple mediums and technological intricacies that are wedded together to achieve a perfect balance between mathematical proportions and aesthetic richness. One example of this amalgamation of creativity and craftsmanship is seen in the Temple architecture of India, which continues to endure the test of time as the place of socio-religious congregation of the people practicing Hinduism. The design and proportions of these temples vary according to geographical location and chronology, but share certain basic concepts that are fundamental to their architecture. The aim of this research paper is to identify and examine these core concepts of structure and organization in the vernacular variants of temple design across the Indian subcontinent.

In order to conceptually understand the form and function of these magnificent structures, it is necessary to comprehend the basic foundations of Hinduism itself. Considered to be one of the oldest religions of the world, Hinduism, which is also known as ‘Sanatana Dharma’, has been founded on the basic premise of acquiring moral values and doing good deeds throughout one’s life in order to attain ‘moksha’ or salvation (Nityanand, 2001, Pg. 6). Unlike most of the religions of the West, Hinduism is polytheistic and accommodates a pantheon of Gods into its realm, each attributed with special powers to resolve specific concerns and problems troubling their adherents. The list of main Gods include Brahma, the creator and his consort Saraswati, the goddess of learning, Vishnu, the preserver and his consort Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth and Shiva, the destroyer and his consort Parvati, the mother goddess, in addition to many others. These gods are believed to reside in the heavens, but take up different human forms (Avatars) from time to time to save their devotees from hurdles they may face in life. Therefore, Temples are venerated as the terrestrial place of residence of these numerous Gods, and are built in a very elaborate and manner, to fit their heavenly stature and purpose (Bharne & Krusche, 2014, Pg. 8).

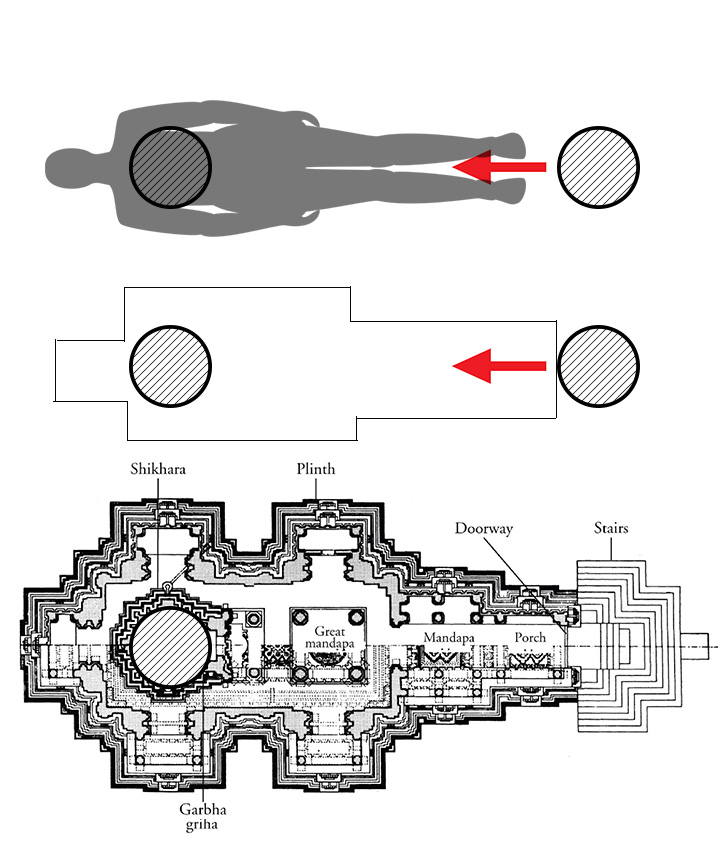

According to the ‘Vastu Shastra’, which is an ancient Hindu treatise on the science of building design, the Gods and the Priests are meant to reside in buildings that are shaped in the form of a ‘Vastu- purusha-mandala’, which can be translated basically into a symmetrical, repeating structure derived from a basic square or rectangular form, with strong attributes of cardinality and human morphology, evident from the plan, section and site plan (Kramrisch & Burnier, 1976, Pg. 20). Arguably, most Hindu temples across India have been built on different stylistic variations of this basic organizing principle, forming complex intersections and patterns to indicate space. In addition to geometric form, the mathematics of proportions also played a very important role in the design of these temples and were regulated by the scriptures. According to Dr. Michael Miester from the University of Pennsylvania, the overall foundations of most Hindu temples have been laid out in a uniform grid arrangement, in accordance with the specifications of a sixth-century text known as the ‘Brhat Samhita’, which were further segregated into smaller grids to create the spaces inside the temple (1983, Pg. 2).

These canons of proportion are easily identifiable from the floor plan of the Kandariya Mahadeva temple located in Khajuraho, in Central India. Built in the 11th century CE, the temple achieves a complex layout due to the periodic intersection and radiation of basic square modules. The foundation of the temple has been laid in the form of a nine square grid, which implies the prominence of the center of the temple as the radiating point of equal and opposite forces, thus creating a perfect balance (Rian, Park, Ahn et al, 2007). In addition, the plan takes the form of a standing human silhouette, which has been utilized to arrange the spaces in accordance with the ‘Vastu-purusha-mandala’, and also to create a constant expansion and contraction of the form, which provides both visual and spatial variation. The human form induces linearity into the temple, which becomes the central pathway through which people traverse in order to reach the deity.

The Hindu temple is organized on the basis of the cardinal directions and the hierarchy of rituals performed. Faithful Hindus revere many natural forms such as air, water, fire, earth and space, however, the biological form they venerate the most is the mountain, as they are believed to be favored by the Gods as their place of residence (Elgood, 2000, Pg. 94). Therefore, the principal form of mountains and caves have been instrumental in shaping the form of Hindu temples. The morphology of these forms, which were initially made to mimic these natural forms, were articulated through time in such a way that they achieved a new level of expression. While the initial temples were carved into actual caves to emphasize the closure provided by the womb and the manifestation of the Gods within, as seen in the Udaigiri temple in Central India, the later temples, such as the Brihadeeshwara temple in Thanjavur, Southern India were crafted to provide devotees with the architectural experience of being a part of and paying obeisance to these natural forms (Meister, 1986, Pg. 35).

The organization of the buildings inside the Temples form an important aspect of their experiential qualities. The earliest existent Temples built in the 6th and 7th centuries AD, such as the Kailasanathar Temple, in Kanchipuram, Southern India exhibit these basic organizational aspects and are believed to have influenced the development of the later Hindu Temples, such as the Lingaraja Temple in Bhubaneshwar, Eastern India, that was built in the 13th century, while only increasing in scale and proportion. The processional entry into the Temple is from the west, facing east through a large gate tower, known as the ‘Ardhamandapa'. This is followed sequentially by a pillared hall, called the ‘Mandapa’, where dance and music performances are held to appease the deity. The devotees are then lead into the innermost sanctum, known as the ’Garbhagriha’ or womb chamber, above which a corbelled, mountain-like form, known as the ‘shikhara’ was constructed. Located right at the heart of the temple, the Garbhagriha houses the shrine of the residing deity, and is where prayers are conducted ritually all through the day (Cartwright, 2015).

In recent times, temples continue to follow the essential characteristics of positioning, organization and planning, and resonate the external forms, that have been in existence for thousands of years. The Akshardham Temple complex in Delhi, which was inaugurated in 2005, employs very similar patterns of form and organization as the early Hindu temples, with the addition of large pools of water and landscape to provide an atmosphere of serenity in addition to piety (Singh, 2010, Pg. 49). Temples constructed in other parts of the world, such as the Sri Venkateswara Temple in Birmingham, U.K. and the Swaminarayan temple in Atlanta, U.S.A aim to be a spectacle of Indian craftsmanship and grandeur to the foreign eye, while maintaining the core concepts of form and order, as prescribed by tradition.

It is evident from this research paper that the confluence of form space and meaning constitute the entirety of Hindu temple architecture. The paper states that the planar and sectional organization of the Hindu temple is based on the ‘Vastu-purusha-mandala’ which is a basic square form accompanied by certain human characteristics. In addition, it is seen that the form of these Temples is categorized by the mimesis of natural elements like mountains and caves, in order to provide devotees with the experience of praying to the gods at their sacred abode. Moreover, it is seen that a processional route is utilized to facilitate the movement of the faithful from the entry gates of the temple right into the sanctum sanctorum. The research conducted for this paper has thrown some light on a few extraordinary examples of Hindu temple architecture, however the sheer magnitude of the varying vernacular styles and disciplines is numerous and falls beyond the scope and boundaries of this paper. In closing, the paper provides a glimpse of the creativity and mathematical genius of the ancient Indian Temple builders, and how they employed the core architectural principles of form, space and order to put forward their religious sentiments as a method of consecration to their benevolent Gods.

References

Bharne, V., Krusche, K., & Krier, L. (2012). Rediscovering the Hindu temple: The sacred architecture and urbanism of India. Newca upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Pub..

Retrieved from

https://books.google.ae/books?hl=en&lr=&id=CGukBgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR7&dq

Cartwright, M. (2015), Hindu Architecture, Ancient History Encyclopedia.

Retrieved from:

http://www.ancient.eu/Hindu_Architecture/

Kramrisch, S., & Burnier, R. (1976). The Hindu temple (Vol. 1). Motilal Banarsidass Publ.

Retrieved from https://books.google.ae/books?hl=en&lr=&id=NNcXrBlI9S0C&oi=fnd&pg=PA3&dq

Meister, M. (1983). Geometry and Measure in Indian Temple Plans: Rectangular Temples. Artibus Asiae, 44(4), 266-296. Doi: 10.2307/3249613

Retrieved from

http://www.jstor.org/stable/3249613?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

Meister, M. (1986). On the Development of a Morphology for a Symbolic Architecture: India. RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, (12), 33-50.

Retrieved from

http://www.jstor.org/stable/20166752

Nityanand, S. (2001). Hinduism that is Sanatana Dharma. Central Chinmaya Mission Trust.

Retrieved from: https://books.google.ae/books?hl=en&lr=&id=giPbYfAxP7wC&oi=fnd&pg=PA1&dq=+Hinduism+that+is+Sanatana+Dharma

Rian,I., Park, J., Ahn, H. and Chang, D. (2007). Fractal geometry as the synthesis of Hindu cosmology in Kandariya Mahadev temple, Khajuraho, Building and Environment, Volume 42, Issue 12, Pages 4093-4100

Retrieved from:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2007.01.028.

Singh, K. (2010). TEMPLE OF ETERNAL RETURN: THE SWĀMINĀRĀYAN AKSHARDHĀM COMPLEX IN DELHI. Artibus Asiae, 70(1), 47-76.

Retrieved from

http://www.jstor.org/stable/20801632?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents